|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

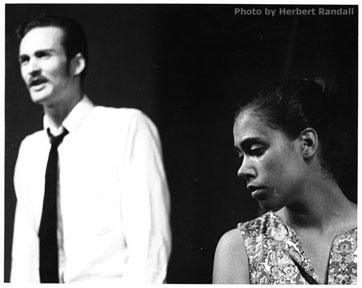

Photo: “ ‘In White America’ performance,”

by Herbert Randall, 1964

Provided by the McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi

Reprinted with permission of Herbert Randall

IN WHITE AMERICA

A DOCUMENTARY PLAY

By Martin B. Duberman

Two Scenes from the Second Act

NARRATOR:

In l866, the Radical Wing of the Republican party gained control of Congress and gave the Negro the right to vote. At once, the Ku Klux Klan rose to power in the South . . .

THE HOODED FIGURE:

Before the immaculate Judge of Heaven and Earth, and upon the Holy Evangelists of Almighty God, do, of my own free will and accord, subscribe to the sacredly binding obligation: We are on the side of justice, humanity, and constitutional liberty, as bequeathed to us in its purity by our forefathers. We oppose and reject the principles of the Radical party.

(Music—guitarist)

I hate the Freedmen’s Bureau

And the uniform of blue

I hate the Declaration of Independence, too.

With all its fume and fuss,

And them thievin’, lyin’ Yankees

Well, I hate ‘em wuss and wuss.

NARRATOR:

Acts of violence by the Klan were investigated by the Federal government in a series of hearings and trials.

PROSECUTOR:

What was the purpose of the Ku Klux Klan? What were the raids for?

KLANSMAN:

To put down radicalism, the raids were for.

PROSECUTOR:

In what way were they to put down Radicalism?

KLANSMAN:

It was to whip them and make them change their politics.

PROSECUTOR:

How many raids have you been on by order of the Chief?

KLANSMAN:

Two, sir.

PROSECUTOR:

Now, will you state to the jury what was done on those raids?

KLANSMAN:

Yes, sir. We were ordered to meet at Howl’s Ferry, and went and whipped five colored men. Presley Holmes was the first they whipped and then went on and whipped Jerry Thompson: went then and whipped Charley Good, James Leach and Amos Lowell.

PROSECUTOR:

How many men were on these raids?

KLANSMAN:

I think there was twenty in number.

PROSECUTOR:

How were they armed and uniformed?

KLANSMAN:

They had red gowns and had white covers over their horses. Some had pistols and some had guns.

PROSECUTOR:

What did they wear on their heads?

KLANSMAN:

Something over their heads came down. Some of them had horns on.

PROSECUTOR:

Disguises dropped down over their faces?

KLANSMAN:

Yes, sir.

PROSECUTOR:

What was the object in whipping those five men you have named?

KLANSMAN:

The object in whipping Presley Holmes, was about some threats he had made about him going to be buried in Salem graveyard.

PROSECUTOR:

What was the first to occur?

KLANSMAN:

Well, sir, Webber—he was leading the Klan—ran into the yard and kicked down the door and dragged him out, and led him off about two hundred yards, and whipped him.

PROSECUTOR:

How many lashes did they give him?

KLANSMAN:

I cannot tell you how many.

PROSECUTOR:

Did they whip him severely or not?

KLANSMAN:

His shirt was stuck to his back.

PROSECUTOR:

What occurred at the next place?

KLANSMAN:

They whipped Jerry Thompson at the next place; told him never to go to any more meetings; to stay at home and attend to his own business.

PROSECUTOR:

What was done at the next place?

KLANSMAN:

They went there and whipped Charley Good. They whipped him very severe; they beat him with a pole and kicked him down on the ground.

PROSECUTOR:

What did they tell him?

KLANSMAN:

To let Radicalism alone; if he didn’t his doom would be fatal.

(The lights fade. They come up immediately on another examination. A Negro woman, HANNAH TUTSON, is being questioned.)

LAWYER:

Are you the wife of Samuel Tutson?

MRS. TUTSON:

Yes, sir.

LAWYER:

Were you at home when he was whipped last spring?

MRS. TUTSON:

Yes, sir; I was at home.

LAWYER:

Tell us what took place then, what was done, and how it was done.

MRS. TUTSON:

That night, just as I got into bed, five men bulged right against the door, and it fell in the middle of the floor. George McRae ran right to me. As I saw him coming I took up the child-the baby-and held to him. I started to scream and George McRae catched me by the throat and choked me. And he catched the little child by the foot and slinged it out of my arms. They got me out of doors. The old man was ahead of me, and I saw Dave Donley stamp on him. They carried me to a pine, and then they tied my hands there. They pulled off all my linen, tore it off so that I did not have a piece of rag on me as big as my hand. I said, “Men what are you going to do with me?” They said, “God damn you, we will show you; you are living on another man’s premises.” I said, “No; I am living on my own premises; I gave $150 for it and Captain Buddington and Mr. Mundy told me to stay here.” They whipped me for awhile. Then George McRae would say, “Come here, True-Klux.” Then the True-Klux would step off about as far as (pointing to a member of the committee) that gentleman and whisper; when they came back, they would whip me again. Every time they would go off, George McRae would make me squat down by the pine, and he would get his knees between my legs and say, “Old lady, if you don’t let me have to do with you, I will kill you.” I said, “No”; they whipped me. There were four men whipping me at once.

LAWYER:

How many lashes did they give you in all?

MRS. TUTSON:

I cannot tell you, for they whipped me from the crown of my head to the soles of my fell. I was just raw. After I got away from them that night I ran to my house. My house was torn down. I went in and felt where my bed was. I could not feel my little children and I could not see them.

LAWYER:

Did you find your children?

MRS. TUTSON:

I did next day at 12 o’clock.

LAWYER:

Where were they?

MRS. TUTSON:

They went out into the field.

LAWYER:

Did the baby get hurt—the one you had in your arms when they jerked it away?

MRS. TUTSON:

Yes, sir; in one of its hips. When it began to walk one of its hips was very bad, and every time you would stand it up it would scream. But I rubbed it and rubbed it, and it looks like he is outgrowing it now.

(Music-Guitarist)

You’ve got to cross that lonesome valley,

You’ve got to cross it by yourself.

There ain’t nobody can do it for you,

You’ve got to cross it all alone.

NARRATOR:

Federal investigations were not followed by effective Federal action. From 1878 to 1915 over 3000 Negroes were lynched in the South-a necessary protection, it was said, against Negro rapists. Yet most lynchings were either for no offense or for such causes as “Insult,” “Bad Reputation,” “Running Quarantine,” “Frightening Children by Shooting at Rabbits,” or “Mistaken Identity.”

On January 21, 1907, United States Senator Ben Tillman, of South Carolina, gave his views on the subject from the Senate floor.

SENATOR TILLMAN:

Mr. President, a word about lynching and my attitude toward it. A great deal has been said in the newspapers, North and South, about my responsibility in connection with this matter.

I have justified it for one crime, and one only. As governor of South Carolina I proclaimed that, although I had taken the oath of office to support law and enforce it, I would lead a mob to lynch any man who had ravished a woman.

Mr. President..When stern and sad—faced white men put to death a creature in human form who has deflowered a white woman, they have avenged the greatest wrong, the blackest crime in all the category of crimes.

The Senator from Wisconsin prates about the law. Look at our environment in the South, surrounded, and in a very large number of counties, outnumbered by the negroes—engulfed, as it were, in a black flood of semi-barbarians. For forty years, negroes have been taught the damnable heresy of equality with the white man. Their minds are those of children, while they have the passions and strength of men.

Let us carry the Senator from Wisconsin to the backwoods of South Carolina, put him on a farm miles from a town or railroad, and environed with negroes. We will suppose he has a fair young daughter just budding into womanhood; and recollect this, the white women of the South are in a state of seige. . . .

That Senator’s daughter undertakes to visit a neighbor or is left home alone for a brief while. Some lurking demon who has watched for the opportunity seizes her; she is choked or beaten into insensibility and ravished, her body prostituted, her purity destroyed, her chastity taken from her, and a memory branded on her brain as with a red-hot iron to haunt her night and day as long as she lives.

In other words, a death in life. This young girl, thus blighted and brutalized drags herself to her father and tells him what has happened. Is there a man here with red blood in his veins who doubts what impulses the father would feel? Is it any wonder that the whole countryside arises as one man and with set, stern faces, seek the brute who has wrought this infamy? And shall such a creature, because he has the semblance of a man, appeal to the law? Shall men coldbloodedly stand up and demand for him the right to have a fair trial and be punished in the regular course of justice? So far as I am concerned he has put himself outside the pale of the law, human and divine. He has sinned against the Holy Ghost. He has invaded the holy of holies. He has struck civilization a blow, the most deadly and cruel that the imagination can conceive. It is idle to reason about it; it is idle to preach about it. Out brains reel under the staggering blow and hot blood surges to the heart. Civilization peels off us, any and all of us who are men, and we revert to the original savage type whose impulses under such circumstances has always been to “Kill! Kill! Kill!”

* * * * * *

NARRATOR:

There was no major breakthrough until 1954, when the Supreme Court declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional. Southern resistance to the court’s decision came to a head three years later at Little Rock, Arkansas, when a fifteen-year-old girl tried to go to school at Central high.

GIRL:

The night before I was so excite I couldn’t sleep. The next morning I was about the first one up. While I was pressing my black and white dress-I had made it to wear on the first day of school-my little brother turned on the TV set. They started telling about a large crowd gathered at the school. The man on TV said he wondered if we were going to show up that morning. Mother called from the kitchen where she was fixing breakfast, “Turn that TV off!” She was so upset and worried. I wanted to comfort her so I said, “Mother, don’t worry!”

Dad was walking back and forth, from room to room, with a sad expression. He was chewing on his pipe and he had a cigar in his hand, but he didn’t light either one. It would have been funny, only he was so nervous.

Before I left home, Mother called us into the living room. She said we should have a word of prayer. Then I caught the bus and got off a block from the school. I saw a large crowd of people standing across the street from the soldiers guarding Central. As I walked on, the crowd suddenly got very quiet. For a moment all I could hear was the shuffling of their feet. Then someone shouted, “Here she comes, get ready!” The crowd moved in closer and then began to follow me, calling me names. I still wasn’t afraid. Just a little bit nervous. Then my knees started to shake all of a sudden and I wondered whether I could make it to the center entrance a block away. It was the longest block I ever walked in my whole life.

Even so, I still wasn’t too scared because all the time I kept thinking that the guards would protect me.

When I got right in front of the school, I went up to a guard. He just looked straight ahead and didn’t move to let me pass him. I stood looking at the school-it looked so big! Just then the guards let some white students go through.

The crowd was quiet. I guess they were waiting to see what was going to happen. When I was able to steady my knees, I walked up to the guard who had let the white students in. He too didn’t move. When I tried to squeeze past him, he raised his bayonet and then the other guards closed in and they raised their bayonets.

They glared at me with a mean look and I was very frightened and didn’t know what to do. I turned around and the crowd came toward me.

They moved closer and closer. Somebody started yelling “Lynch her! Lynch her!”

I tried to see a friendly face somewhere in the mob—someone who maybe would help. I looked into the face of an old woman and it seemed a kind face but when I looked at her again, she spat on me.

They came closer, shouting, “No nigger bitch is going to get in our school. Get out of here!” Then I looked down the block and saw a bench at the bus stop. I thought, “If I can only get there I will be safe.” I don’t know why the bench seemed a safe place to me, but I started walking toward it. I tried to close my mind to what they were shouting, and kept saying to myself, “If I can only make it to the bench I will be safe.”

When I finally got there, I don’t think I could have gone another step. I sat down and the mob crowded up and began shouting all over again. Someone hollered, “Drag her over to the tree! Let’s take care of the nigger.” Just then a white man sat down beside me, put his arm around me and patted my shoulder.

(During last part of the speech, white actor sits beside her on bench.)

WHITE MAN:

She just sat there, her head down. Tears were streaming down her cheeks. I don’t know what made me put my arm around her, saying, “Don’t let them see you cry.” Maybe she reminded me of my 15-year-old daughter.

Just then the city bus came and she got on. She must have been in a state of shock. She never uttered a word.

GIRL:

I can’t remember much about the bus ride, but the next thing I remember I was standing in front of the School for the Blind, where Mother works. I ran upstairs and I kept running until I reached Mother’s classroom.

Mother was standing at the window with her head bowed, but she must have sensed I was there because she turned around. She looked as if she had been crying, and I wanted to tell her I was all right. But I couldn’t speak. She put her arms around me and I cried.

WHITE ACTOR (sings):

They say down in Hines County

No neutrals can be met,

You’ll be a Freedom Rider,

Or a thug for Ross Barnett.

(WHOLE CAST, looking at each other, not the audience, quietly sings four lines of “Which Side Are You On”)

NARRATOR:

After 1957, the Negro protest exploded-bus boycotts, sit-ins, Freedom Rides, drives for voter registration, job protests.

NEGRO MAN:

After 400 years of barbaric treatment, the American Negro is fed up with the unmitigated hypocrisy of the white man.

WHITE MAN:

The Negroes are demanding something that isn’t so unreasonable.

NEGRO MAN:

To have a cup of coffee at a lunch counter.

WHITE MAN:

To get a decent job.

NEGRO WOMAN:

The American Negro has been waiting upon voluntary action since 1876.

WHITE MAN:

If the thirteen colonies had waited for voluntary action this land today would be part of the British Commonwealth.

WHITE WOMAN:

The demonstrations will go on for the same reason the thirteen colonies took up arms against George III.

NEGRO MAN:

For like the colonies we have beseeched.

NEGRO WOMAN:

We have implored.

NEGRO MAN:

We have supplicated.

NEGRO MAN:

We have entreated.

NEGRO WOMAN:

We are writing our declaration of independence in shoe leather instead of ink.

WHITE MAN:

We’re through with tokenism and gradualism and see-how-far-you’ve-comeism.

WHITE MAN:

We’re through with we’ve-done-more-for-your-people-than-anyone-elseism.

NEGRO WOMAN:

We can’t wait any longer.

NEGRO MAN:

Now is the time.

WHITE ACTOR

(stepping forward, reads from document):

We the people of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union...

|

WHITE ACTOR (con’t): . . . establish justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America..., |

NEGRO ACTRESS (sings under “We the People...,” slowly building in volume):

Oh, Freedom

Oh, Freedom-

Oh, Freedom over me!

And before I’ll be a slave

I’ll be buried in my grave |

WHOLE CAST:

. . . And go home to my Lord and be free

Duberman, Martin B., In White America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1964.

(First Scene: The Klan, p43-52; Second Scene: Little Rock, p 64-69.)

Copyright Martin Duberman, 1964

Reprinted with kind permission of Martin Duberman.