|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

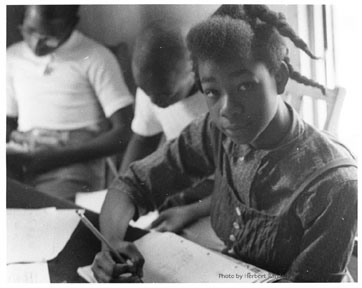

Photo: “Writing in Freedom School,”

by Herbert Randall, 1964

Provided by the McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi

Reprinted with permission of Herbert Randall

FREEDOM SCHOOL DATA

Council of Federated Organizations

1017 Lynch Street

Jackson, Mississippi

Press phone: 385-3276

a.) Background on Freedom Schools: the Freedom Schools were proposed late in 1963 by Charles Cobb, a Howard University student until he joined the SNCC staff and “a gifted creative writer,” according to Freedom School Director Professor Staughton Lynd. That “help from outside Mississippi is needed if the Negro youngster were to have any chance of access to a larger world” was an obvious fact, according to Lynd, after preliminary studies of the Mississippi educational system. In Mississippi: The Closed Society, James Silver noted that the per capita expenditure of the Mississippi local schools boards for the white child is almost four times the figure for the Negro child. More than the statistics, the limited subject matter available for study to Mississippi Negro students, the fear of dismissal that restrains their teachers from exploring controversial topics demonstrated that if Mississippi’s Negroes were to take part in an academic process it would have to be in a context supplemental to the schooling available through the state.

b.) Freedom Schools Operation: As of July 26, there were 41 functioning Freedom Schools in twenty communities across the state with an enrolment of 2,135 students—twice the figure projected in planning for the summer. There are approximately 175 teaching full-time in the Freedom Schools, with recruitment of 50 to 100 more in process.

The typical Freedom School has an enrollment of 25 to 100 and a staff of five to six teachers, and is held in a church basement or sometimes the church itself, often using the outdoor area as well. Typically, the morning will be taken up with a “core curriculum” build around Negro History and citizenship. The late morning or afternoon is taken up with special classes (such as French or typing—both very popular) or projects (such as drama or the school newspaper). In the evening classes are held for adults or teen-agers who work during the day.

The idea of the school is centered on discussion of the group. One suggested guide distributed by COFO to Freedom School teachers noted, “In the matter of classroom procedure, questioning is the vital tool. It is meaningless to flood the student with information he cannot understand; questioning is the path to enlightenment. It requires a great deal of skill and tact to pose the question that will stimulate but not offend, lead to unself-consciousness and the desire to express thought. . . . The value of the Freedom Schools will derive mainly from what the teachers are able to elicit from the students in terms of comprehension and expression of their experiences.”

At a time when the nation’s educators have become concerned—and stymied—by bringing to children of the non-verbal “culturally deprived” community the ability to formulate questions and articulate perceptions, the daily pedagogical revolutions that are the basis of any success in a Freedom School classroom become overwhelming upon considering that the students are Mississippi Negroes—possibly the single most deprived group in the nation—and the teachers are culturally alien products of the much-maligned liberal arts undergraduate education. An indication of what is happening among the students and their young teachers in the Freedom Schools is given by a single line of COFO advice given to the teachers: “The formal classroom approach is to be avoided; the teacher is encouraged to use all the resources of his imagination.”

According to Director Lynd, the Freedom Schools may be dealt with in the context of three general situations: a) rural areas; b) urban areas where the civil rights movement has been strong; c) urban areas where the movement has been weak. “In the first and third situations,” analyzes Lynd, “the Freedom Schools have been most successful, not just in numbers, but in what is going on there.”

In the rural areas where there is little recreation or diversion available to the Negro community, the Freedom School becomes the center of teen-age social activities, according to Lynd. Lynd draws upon the Holmes County and Carthage Freedom Schools as examples of this rural success. When the Freedom School staff arrived in Carthage, the entire Negro community was assembled at the church to greet them; when, two days later, the staff was evicted from its school, the community again appeared with pickup trucks to help move the library to a new school site. As this is being written, the Carthage Community, with the help of summer volunteers and a National Council of Churches minister, is building its own community center which will be staffed by civil rights workers and local volunteers.

An example of the second situation, the urban success, is the Hattiesburg Freedom School system, which Lynd refers to as the “Mecca of the Freedom School world.” In Hattiesburg there are more than 600 students in five schools. Each teacher has been told to find a person from the community to be trained to take over his teaching job at the end of the summer. Much of the second session in Hattiesburg will be devoted to the training of local Freedom School teachers. “Here, as in Canton,” states Lynd, “there can be no doubt that the success of the schools stemmed from the intensive civil rights campaign in the community during the months of late winter and spring.”

In Gulfport and Greenville, urban environments with alternative attractions, the movement has not been strong enough in the past to counteract traditional time-passing activities. Lynd notes, however, that the generalization has exceptions. Holly Springs, an urban area in which the movement has not been strong in the past, has a highly successful Freedom School.

It should also be noted that in Holly Springs, Carthage, and Shaw, the Freedom Schools are competing against the regular public school which are currently in session as public schools close in early spring to allow students to chop cotton.

In Mississippi’s stronghold of organized terror, the Southwest, the McComb Freedom School has proven the political value of the schools as an instrument for building confidence in the Negro community when canvassing is impractical. Lynd cites the instance of Miss Joyce Brown’s poem concerning the Freedom School held at a bombed home which moved the community to provide a meeting place for the school. “Thus”, notes Lynd, “the presence of a Freedom School helped to loosen the hard knot of fear and to organize the Negro community.” There are 108 students at the McComb Freedom School.

c) The Future of the Freedom Schools: The Freedom Schools will continue beyond the end of the Summer Project in August. Freedom Schools in several areas are already running jointly with the regular public school session. The Freedom Schools offer subjects—such as foreign languages—not offered in the regular schools, and students are attracted to the informal questioning spirit of the Freedom Schools and academics based around their experiences as Mississippi Negroes. In situations like McComb, the Freedom School has proven its value to the over-all COFO political program as an organizing instrument. Also, among the various COFO programs, the Freedom School project is the one which holds out a particular hope of communication with the white community. In at least two situations, Vicksburg and Holly Springs, white children have attended for short periods. Another factor in the decision to continue the Freedom Schools is the possibility-turned-probability that the Mississippi legislature will offer private school legislation designed to sidestep public school integration (already ordered for the fall of 1964 in Jackson, Biloxi, and Leake County). One is faced by situations such as that in Issaquena County, where there are no Negro public schools and children must be transported into other counties. The backwardness of Mississippi’s educational system in the context of racial discrimination is demonstrated by the fact that in many areas the impact of the 1954 Supreme Court decision that separate cannot be equal was to have separate schools erected for the first time; the step previous to school segregation is concluding that Negro Children should be educated. The rural hard-core area of Issaquena County is an example of a prolonged holdout. A final but not secondary factor is the “widespread apprehension among Mississippi Negroes as to what will happen to them when the Summer Project volunteers leave.” Staughton Lynd adds, “We want to be able to tell them that the program will not end, that momentum cumulated during the summer months will not be permitted to slack off.”

The long-range Freedom School program will be carried on through evening classes in local community centers. “Already in many communities Freedom School and Community Center programs are combined and often in the same building,” according to Lynd. One source of teachers for the continuing Freedom School program will be volunteers who decide to stay beyond the summer; if only one in five stayed, fifty teachers would remain in the state. Another source would be Southern Negro students coming in under the work-study program which provides them with a one-year scholarship to Tougaloo College after one year’s full-time work for SNCC. Other teachers would come through the local communities, under programs of training such as that which has already begun in Hattiesburg. Teachers could also be provided from the ranks of full-time SNCC staff members; in areas such as McComb where the movement can’t register American citizens as voters, civil rights workers can teach in Freedom Schools. There is no doubt but that, in Professor Lynd’s words, “It is a political decision for any parent to let his child come to a Freedom School.”

The Freedom School program can develop as an aid in enabling Mississippi Negro students to make the transition from a Mississippi Negro high school to higher education. Standardized tests will be administered to the most promising Freedom School students under the direction of the College Entrance Examination Board (CEEB) in mid-August. Evaluation of these scores and other data by the National Scholarship Service Fund for Negro Students will lead some of the Freedom School students to a program involving a) a transitional educational experience during the summer after high school, b) a reduced load during the freshman year at college, and c) financial aid. Others can be helped by the already-existing work-study program.

d) Free Southern Theater: As the second Freedom School session (August 3-21) begins, a tour of the Freedom Schools throughout the state is scheduled for the Free Southern theater production of In White America. The Free Southern Theater was organized early this year by SNCC with the assistance of COFO and Tougaloo College as an attempt to “stimulate thought and a new awareness among Negroes in the deep South,” and “will work toward the establishment of permanent stock and repertory companies, with mobile touring units, in major population centers throughout the South, staging plays that reflect the struggles of the American Negro . . . before Negro and, in time, integrated audiences,” according to a Free Southern Theater prospectus. An apprenticeship program is planned which will send a number of promising participants to New York for more intensive study. The company will include both professional and amateur participants.

The development of the Free Southern Theater was sparked by the “cultural desert” resulting from the closed society’s restriction of the patterns of reflective and creative thought.

Each performance of In White America will be accompanied by theater workshops in the Freedom Schools designed to introduce students to the experience of theater through participation. As the classroom methods of the Freedom School are revolutionary in the context of traditional American patterns of education, so the Free Southern Theater brings a new concept of drama to these Mississippi students. Dr. Lynd comments that the aim of the Theater “is the creation of a fresh theatrical style which will combine the highest standards of craftsmanship with a more intimate audience rapport than modern theater usually achieves.”

Segregated school, controlled textbooks, lack of discussion of controversial topics, the nature of the mass media in Mississippi demand the development of a cultural program, to be viewed in the context of education, among an entire people.

Among the objectives listed for the Free Southern Theater by its originators are “to acquaint Southern peoples with a breadth of experience with the theater and related art forms; to liberate and explore the creative talent and potential that is here as well as to promote the production of art; to bring in artists from outside the state as well as to provide the opportunity for local people with creative ability to have experience with the theater; to emphasize the universality of the problems of the Negro people; to strengthen communication between Southern Negroes; to assert that self-knowledge and creativity are the foundations of human dignity.”

Among the sponsors of the Free Southern Theater are singer Harry Belafonte, authors James Baldwin and Langston Hughes, performers Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, and Theodore Bikel, and Lincoln Kirstein, general director of the New York City Ballet.

The proposal for the Free Southern Theater originated with SNCC workers Doris Derby, Gilbert Moses, and John O’Neal, and Tougaloo drama instructor William Hutchinson.

e) Mississippi Summer Caravan of Music: Approximately 25 performing artists, including Pete Seeger, the Chad Mitchell Trio, Theodore Bikel, and SNCC’s Freedom Singers, will have toured the Mississippi Summer Project Freedom Schools and Community Centers before the close of the summer. During the day they will teach in Freedom School workshops, and perform in community concerts in the evening. Communities throughout the state have already been visited by the Caravan.

The Caravan is sponsored by the New York Council of Performing Artists (Gil Turner, Chairman) and is directed by Bob Cohen at the Mississippi Summer Project Headquarters.

f) Excerpts from Freedom School Newspapers: The first ones to insist upon connecting the Freedom Schools to the opening of the closed society of segregated Mississippi are the young students of the Freedom Schools. The average author of a Freedom School newspaper article is between 13 and 15 years of age.

The cover of the first issue of the McComb Freedom School’s “Freedom Journal” depicts a Negro in chains with a scroll below him reading, “Am I not a man and a brother?” One girl, in the same paper, remarks, “. . . too long others have done our speaking for us. . . .” Her mother is a domestic who fears for what will happen to the family due to her child’s attendance at the Freedom School. One 15-year-old student there remarked that the Freedom School “enables me to know that I can get along with the whites and they can get along with me without feeling inferior to each other.”

Two young students in the Holly Springs Freedom School describe their hometown: “The working conditions are bad. The wages are very low. The amount paid for plowing a tractor all day is three dollars. . . . The white man buys most of the supplies used for the annual crops, but the Negro contributes all the labor. In the fall of the year when the crop is harvested and the cotton is sold to market, the white man gives the Negro what he thinks he needs, without showing the Negro a record of the income the white man has collected from the year. This process of farming has become a custom. This way of livelihood is not much different from slavery.”

A student describes her life in the “Benton County Freedom Train:” “We work eight to nine hours each day and are paid daily after work is over. We get only $3.00 per day . . . and . . . chop cotton 81/2 hours to 9 hours each day. . . . The man whom we worked for is responsible for having fresh cold water handy in the field for the workers to drink. The whites also fail to take us to the store in time to eat dinner. . . . When it’s harvest Negroes pick cotton by hand at $2.00 for a hundred pounds and some places $3.00 per hundred.”

In the Mt. Zion Freedom School’s “Freedom Press,” a girl states she comes to the Freedom School because “I want to become a part of history also.”

Joyce Brown, the 15-year-old author of “The House of Liberty” will be a senior next year at McComb’s Negro Burgland High School. When she was 12 years of age she was doing voter registration canvassing when Bob Moses, director of the Mississippi Summer Project, first began voter activities in Mississippi for SNCC in 1961.

The document is from:

SNCC, The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Papers, 1959-1972 (Sanford, NC: Microfilming Corporation of America, 1982) Reel 67, File 340, Page 1183.

The original papers are at the King Library and Archives, The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, Atlanta, GA