|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

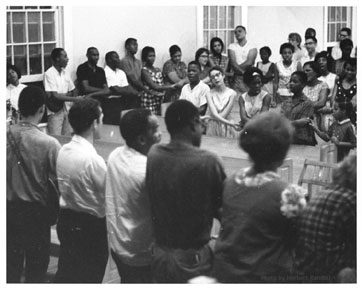

Photo: “We Shall Overcome,”

by Herbert Randall, 1964

Provided by the McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi

Reprinted with permission of Herbert Randall

PROSPECTUS FOR THE MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM SUMMER

“It can be argued that in the history of the United States democracy has produced great leaders in great crises. Sad as it may be, the opposite has been true in Mississippi. As yet there is little evidence that the society of the closed mind will ever process the moral resources to reform itself, or the capacity for self-examination, or even the tolerance of self-examination.”

From Mississippi: The Closed Society

By James W. Silver

It has become evident to the civil rights groups involved in the struggle for freedom in Mississippi that political and social justice cannot be won without the massive aid of the country as a whole, backed by the power and authority of the federal government. Little hope exists that the political leaders of Mississippi will steer even a moderate course in the near future (Governor Johnson’s inaugural speech notwithstanding); in facts, the contrary seems true: as the winds of change grow stronger, the threatened political elite of Mississippi becomes more intransigent and fanatical in its support of the status quo. The closed society of Mississippi is, as Professor Silver asserts, without the moral resources to reform itself. And Negro efforts to win the right to vote cannot succeed against the extensive legal weapons and police powers of local and state officials without a nationwide mobilization of support.

A program is planned for this summer which will involve the massive participation of Americans dedicated to the elimination of racial oppression. Scores of college students, law students, medical students, teachers, professors, ministers, technicians, folk artists and lawyers from all over the country have already volunteered to work in Mississippi this summer—and hundreds more are being recruited.

Why a project of this size?

1. Projects of the size of those of the last three summers (100 to 150 workers) are rendered ineffective quickly by police threats and detention of members.

2. Previous projects have gotten no national publicity on the crucial issue of voting rights and, hence, have little national support either from public opinion or from the federal government. A large number of students from the North making the necessary sacrifices to go South would make abundantly clear to the government and the public that this is not a situation which can be ignored any longer, and would project an image of cooperation between Northern and white people and Southern Negro people to the nation which will reduce fears of an impending race war.

3. Because of the lack of numbers in the past, all workers in Mississippi have had to devote themselves to voter registration, leaving no manpower for stopgap community education projects which can reduce illiteracy as well as raise the level of education of Negroes. Both of these activities are, naturally, essential to the project’s emphasis on voting.

4. Bail money cannot be provided for jailed workers; hence, a large number of people going South would prevent the project from being halted in its initial stages by immediate arrests. Indeed, what will probably happen in some communities is the filling of jails with civil rights workers to overflowing, forcing the community to realize that it cannot dispense with the problem of Negroes’ attempting to register simply by jailing “outsiders”.

Why this summer?

Mississippi at this juncture in the movement has received too little attention—that is, attention to what the state’s attitude really is—and has presented COFO with a major policy decision. Either the civil rights struggle has to continue, as it has in the past few years, with small projects in selected communities with no real progress on any fronts, or there must be a task force of such a size as to force either the state and the municipal governments to change their social and legal structures, or the federal government to intervene on behalf of the constitutional rights of its citizens.

Since 1964 is an election year, the clear-cut issue of voting rights should be brought out in the open. Many SNCC and CORE workers in Mississippi hold the view that Negroes will never vote in large numbers until federal marshals intervene. At any rate, many Americans must be made to realize that the voting rights they so often take for granted involve considerable risk for Negroes in the South. In the larger context of the national civil rights movement, enough progress has been made during the last year that there can be no turning back. Major victories in Mississippi, recognized as the stronghold of racial intolerance in the South, would speed immeasurably the breaking down of legal and social discrimination in both North and South.

The project is seen as a response to the Washington March and an attempt to assure that in the Presidential election year of 1964 all American citizens are given the franchise. The people at work on the project are neither working at odds with the federal government nor at war with the State of Mississippi. The impetus is not against Mississippi but for the right to vote, the ability to read, the aspirations and the training to work.

Direction of the Project:

This summer’s work in Mississippi is sponsored by COFO, the Council of Federated Organizations, which includes the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the NAACP, as well as Mississippi community groups. Within the state COFO has made extensive preparations since mid-January to develop structured programs which will put to creative use the talents and energies of the hundreds of expected summer volunteers.

Voter Registration: This will be the most concentrated level of activity. Voter registration workers will be involved in an intensive summer drive to encourage as many Negroes as possible to register. They will participate in COFO’s Freedom Registration, launched in early February, to register over 400,000 Negroes on Freedom Registration books. These books will be set up in local Negro establishments and will have simplified standards of registration (literacy test and the requirement demanding an interpretation of a section of the Mississippi Constitution will be eliminated). Freedom Registration books will serve as the basis of a challenge of the official books of the state and the validity of “official” elections this fall. Finally, registration workers will assist in the campaigns of Freedom candidates, who are expected to run for seats in all five of the State’s Congressional districts and for the seat of Senator John Stennis, who is up for re-election.

Freedom Schools:

1. General Description. About 25 Freedom Schools are planned, of two varieties: day schools in about 20-25 towns (commitments still pending in some communities) and one or two boarding, or residential, schools on college campuses. Although the local communities can provide school buildings, some furnishings, and staff housing (and, for residential schools, student housing), all equipment, supplies and staff will have to come from outside. A nationwide recruitment program is underway to find and train the people and solicit the equipment needed. In the schools, the typical day will be hard study in the morning, an afternoon break (because it’s too hot for an academic program) and less formal evening activities. Because the afternoons are free, students will have an opportunity to work with the COFO staff in other areas of the Mississippi Freedom Summer program, and the additional experience will enrich their contribution to the Freedom School sessions.

a. Day Schools. The day schools will accommodate about 50 students, with a staff of 15. There are 20 communities, located in all five Congressional districts of the state, where the people in the community have indicated that they want a Freedom School and are cooperating in finding facilities and housing. These are the towns of some size, where the local Negro communities can provide housing for the staff, and where a suitable building can be located and safely leased. The day schools will attract high-school students from the immediate area only, since there are no provisions planned for living in, but there will be organized contacts—exchanges, sports events, etc.—between day Freedom Schools across the State. The sessions will present similar but not identical material, so the students can profitably attend one or both sessions. This will allow some adjustment for students who must work during the cotton-picking season, and faculty people who are unable to stay six weeks.

b. Boarding Schools. The one or two boarding schools will accommodate 150 to 200 students apiece, in a college-campus atmosphere. There will be one six-week session of the boarding schools. The curriculum will be similar to that of the day schools, but on a more intensive level, and with an additional goal of bringing together and training high-quality student leadership. The boarding schools will recruit students who have displayed some leadership potential and can profit form the more intensive approach.

c. Curriculum. The aim of the Freedom Schools’ curriculum will be to challenge the student’s curiosity about the world, introduce him to his particularly “Negro” cultural background, and teach him basic literacy skills in one integrated problem. That is, the students will study problem areas in the world, such as the administration of justice or the relation between state and federal authority. Each problem area will be built around a specific episode which is close to the experience of Mississippi students. The whole question of the court system, and the place of law in our lives, with many relevant ramifications, can be dealt with in connection with the study of how one civil rights case went through the courts and was ultimately decided in favor of the defendant. The episode of Congressman Jamie Whitten’s tractor deal, where Whitten quashed a federal program to train over 2,000 tractor drivers in the Mississippi Delta (because it would have been integrated), can lead one into the whole area of state and federal relations. The campaign of Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer for Congress (running against Jamie Whitten) provides a basis for studying all the forces which are against her, and which have worked against a Negro’s even attempting to run for Congress in Mississippi. Planning the COFO project to challenge the regular Mississippi delegation at the Democratic National Convention provides the starting-point for a study of the whole Presidential nomination and election procedures. These and other “case studies” which are used to explore larger problem areas in society will be offered to the students. The Negro history outline, as presently planned, will be divided into sections to be coordinated with the problem-area presentation. In this context, students will be given practice activities to improve their skills with reading and writing. Writing press releases, leaflets, etc., for the political campaigns is one example. Writing affidavits and reports of arrests, demonstrations, trials, etc., which occur during the summer in their towns, will be another. Using the telephone as a campaign tool will both help the political candidates and help students to improve their techniques in speaking effectively in a somewhat formal situation. By using a multidimensional, integrated program, the curriculum can be more easily absorbed into the direct experience of the students.

d. Students. Students for the Freedom Schools will be recruited through established contacts with ministers, educators, and other organizational contacts in the state. Around a hundred applications have already been returned, and we do not anticipate that written applications will form the bulk of the students selected. A statewide student organization, the Mississippi Student Union, has recently been formed, and will be important to the recruitment of students. Students who have shown evidence of leadership potential will be encouraged to attend the state-wide boarding schools, to meet students form other parts of the state, and lay the foundation of a much broader student movement.

e. Staff. Both professional and nonprofessional teachers will participate in the staffing of the schools. Professional teachers will be sponsored by the professional teachers’ associations, the National Council of Churches, the Presbyterian Church and other institutions with educational resources. The nonprofessional teachers will be selected from among the applicants for the summer project. A special delegation of Chicago high-school students, who have taught Negro history to other students their own age under the auspices of Chicago’s Amistad Society, will work as student teachers in the Negro history program.

f. Schedule. The boarding-school staff and staff for the first session of the day schools will go through a general orientation program with the community center staff, probably held at Mt. Beaulah. This orientation will run July 8-12. On July 13, the boarding schools and the first session of the day schools will receive students. Orientation for the teaching staff of the second session of the day schools will be held August 5-9. On August 10, the second session of the day schools will start classes. The sessions will end on August 22 for the boarding school and August 30 for the second-session day school.

Community Centers: The community centers program projects a network of community centers across the state. Conceived as along-range institution, these centers will provide a structure for a sweeping range of recreational and educational programs. In doing this, they will not only serve basic needs of Negro communities now ignored by the social service provisions of the State, but will form a dynamic focus for the development of community organization. The educational features of centers will include job-training programs for the unskilled and unemployed, literacy and remedial programs for adults as well as young people, public health programs such as prenatal and infant care, basic nutrition, etc., to alleviate some of the serious health problems of Negro Mississippians, adult education workshops which would deal with family relations, federal service programs, home improvement and other information vital to the needs of Negro communities, and also extracurricular programs for grade-school and high-school students to supplement educational deficiencies and provide opportunity for critical thought and creative expression. Each center would have a well-rounded library because Negroes in many communities now have no access to an adequate library.

Though the community centers program is primarily educational, some of each center’s resources would be used to provide much-needed recreational facilities for the Negro community. In most communities in Mississippi the only recreation outside of taverns is the movies, and for Negroes this means segregated movies. If there is a movie theater in the Negro community, it is old, run-down, and shows mostly out of date, third-rate Hollywood films. The film program of the centers will not only provide a more agreeable atmosphere for movies; it will bring films of serious content which are almost never shown in Mississippi, where ideas are rigidly controlled. Other recreational offerings will be music appreciation classes, arts and crafts workshops, drama groups, discussion clubs on current events, literature and Negro achievement, etc., pen-pal clubs, organized sports (where equipment allows), and occasional special performances by outside entertainers, such as folk festivals, jazz concerts, etc.; organized storytelling for young children will be entertaining, and will introduce them to the resources of the center’s library and to reading for pleasure in general.

Special Projects:

a. Research Project—A number of summer workers will devote themselves to research on the economic and political life of Mississippi. Some of this work can be done outside the state, but much will need resources which can be found only in Mississippi. In addition, a number of people will be asked to live in white communities to survey attitudes and record reactions to summer happenings.

b. Legal Projects—A team of lawyers and at least 100 law students are expected to come to Mississippi to launch a massive legal offensive against the official tyranny of the State of Mississippi. Law students will be dispersed to projects around the State to serve as legal advisers to voter registration workers and to local people. Others will be concentrated in key areas where they will engage in legal research and begin to prepare suits against the State and local officials and to challenge every law that deprives Negroes of the freedom.

c. White Communities—Until now there has been no systematic attempt by people interested in the elimination of hate and bigotry to work within the white communities of the Deep South. It is the intention of the Mississippi Summer Projects to do just that. In the past year, a significant number of Southern white students have been drawn into the movement. Using students form upper Southern states such as Tennessee, and occasionally native Mississippians, SNCC hopes to develop programs within Mississippi’s white community. These programs will deal directly with the problems of the white people. While almost all Negroes in Mississippi are denied the right to vote, statistics clearly indicate that a majority of whites are excluded as well. In addition, poverty and illiteracy can be found in abundance among Mississippi whites. There is in fact a clear area for Southern white students to work in, for in many ways Mississippi has imprisoned her white people along with her blacks. This project will be pilot and experimental and the results are unpredictable. But the effort to organize and educate whites in the direction of democracy and decency can no longer be delayed.

d. The Theater Project—Sponsored by the Tougaloo Drama Department, this summer will also mark the beginning of a repertory theater in Jackson, Mississippi. The actors will be Negro Mississippians; the plays will dramatize the experience of the Negro in Mississippi and in America; the stage will be the churches, community centers and fields of rural Mississippi.

Using the theater as an instrument of education as well as a source of entertainment, a new area of protest will be opened.

The document is from:

SNCC, The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Papers, 1959-1972 (Sanford, NC: Microfilming Corporation of America, 1982) Reel 39, File 190, Page 1039.

The original papers are at the King Library and Archives, The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, Atlanta, GA